| |

|

| |

| |

|

The

word ‘helminth’ is a general term meaning ‘worm’,

but there are many different types of worms. Prefixes are

therefore used to designate types: platy-helminths for flat-worms

and nemat-helminths for round-worms. All helminths are multicellular

eukaryotic invertebrates with tube-like or flattened bodies

exhibiting bilateral symmetry. They are triploblastic (with

endo-, meso- and ecto-dermal tissues) but the flatworms are

acoelomate (do not have body cavities) while the roundworms

are pseudocoelomate (with body cavities not enclosed by mesoderm).

In contrast, segmented annelids (such as earthworms) are coelomate

(with body cavities enclosed by mesoderm).

Many helminths

are free-living organisms in aquatic and terrestrial environments

whereas others occur as parasites in most animals and some

plants. Parasitic helminths are an almost universal feature

of vertebrate animals; most species have worms in them somewhere.

Biodiversity

Three

major assemblages of parasitic helminths are recognized: the

Nemathelminthes (nematodes) and the Platyhelminthes (flatworms),

the latter being subdivided into the Cestoda (tapeworms) and

the Trematoda (flukes): |

nematode |

cestode |

trematode |

|

|

|

|

|

> |

Nematodes

(roundworms) have long thin unsegmented tube-like bodies

with anterior mouths and longitudinal digestive tracts.

They have a fluid-filled internal body cavity (pseudocoelum)

which acts as a hydrostatic skeleton providing rigidity

(so-called ‘tubes under pressure’). Worms

use longitudinal muscles to produce a sideways thrashing

motion. Adult worms form separate sexes with well-developed

reproductive systems. |

| |

|

|

| |

> |

Cestodes

(tapeworms)

have long flat ribbon-like bodies with a single anterior

holdfast organ (scolex) and numerous segments. They

do not have a gut and all nutrients are taken up through

the tegument. They do not have a body cavity (acoelomate)

and are flattened to facilitate perfusion to all tissues.

Segments exhibit slow body flexion produced by longitudinal

and transverse muscles. All tapeworms are hermaphroditic

and each segment contains both male and female organs. |

| |

|

|

| |

> |

Trematodes

(flukes) have small flat leaf-like bodies with oral

and ventral suckers and a blind sac-like gut. They do

not have a body cavity (acoelomate) and are dorsoventrally

flattened with bilateral symmetry. They exhibit elaborate

gliding or creeping motion over substrates using compact

3-D arrays of muscles. Most species are hermaphroditic

(individuals with male and female reproductive systems)

although some blood flukes form separate male and female

adults. |

| |

|

|

|

Unlike

other pathogens (viruses, bacteria, protozoa and fungi), helminths

do not proliferate within their hosts. Worms grow, moult,

mature and then produce offspring which are voided from the

host to infect new hosts. Worm burdens in individual hosts

(and often the severity of infection) are therefore dependent

on intake (number of infective stages taken up). Worms develop

slowly compared to other infectious pathogens so any resultant

diseases are slow in onset and chronic in nature. Although

most helminth infections are well tolerated by their hosts

and are often asymptomatic, subclinical infections have been

associated with significant loss of condition in infected

hosts. Other helminths cause serious clinical diseases characterized

by high morbidity and mortality. Clinical signs of infection

vary considerably depending on the site and duration of infection.

Larval and adult nematodes lodge, migrate or encyst within

tissues resulting in obstruction, inflammation, oedema, anaemia,

lesions and granuloma formation. Infections by adult cestodes

are generally benign as they are not invasive, but the larval

stages penetrate and encyst within tissues leading to inflammation,

space-occupying lesions and organ malfunction. Adult flukes

usually cause obstruction, inflammation and fibrosis in tubular

organs, but the eggs of blood flukes can lodge in tissues

causing extensive granulomatous reactions and hypertension.

Life-cycles

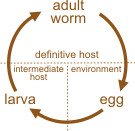

Helminths

form three main life-cycle stages: eggs, larvae and adults.

Adult worms infect definitive hosts (those in which sexual

development occurs) whereas larval stages may be free-living

or parasitize invertebrate vectors, intermediate or paratenic

hosts. Nematodes produce eggs that embryonate in utero or

outside the host. The emergent larvae undergo 4 metamorphoses

(moults) before they mature as adult male or female worms.

Cestode eggs released from gravid segments embryonate to produce

6-hooked embryos (hexacanth oncospheres) which are ingested

by intermediate hosts. The oncospheres penetrate host tissues

and become metacestodes (encysted larvae). When eaten by definitive

hosts, they excyst and form adult tapeworms. Trematodes have

more complex life-cycles where ‘larval’ stages

undergo asexual amplification in snail intermediate hosts.

Eggs hatch to release free-swimming miracidia which actively

infect snails and multiply in sac-like sporocysts to produce

numerous rediae. These stages mature to cercariae which are

released from the snails and either actively infect new definitive

hosts or form encysted metacercariae on aquatic vegetation

which is eaten by definitive hosts. |

nematode

cycle

egg - larvae (L1-L4) - adult |

cestode

cycle

egg - metacestode - adult |

trematode

cycle

egg-miracidium-sporocyst-redia-cercaria-(metacercaria)-adult |

|

|

|

|

Helminth

eggs have tough resistant walls to protect the embryo while

it develops. Mature eggs hatch to release larvae either within

a host or into the external environment. The four main modes

of transmission by which the larvae infect new hosts are faecal-oral,

transdermal, vector-borne and predator-prey transmission: |

faecal-oral

|

trasdermal

|

vector-borne

|

predator-prey

|

|

| |

|

|

|

> |

faecal-oral

transmission

of

eggs or larvae passed in the faeces of one host and

ingested with food/water by another (e.g. ingestion

of Trichuris eggs leads directly to gut infections

in humans, while the ingestion of Ascaris eggs

and Strongyloides larvae leads to a pulmonary

migration phase before gut infection in humans). |

| |

|

|

| |

> |

transdermal

transmission

of

infective larvae in the soil (geo-helminths) actively

penetrating the skin and migrating through the tissues

to the gut where adults develop and produce eggs that

are voided in host faeces (e.g. larval hookworms penetrating

the skin, undergoing pulmonary migration and infecting

the gut where they feed on blood causing iron-deficient

anaemia in humans). |

| |

|

|

| |

> |

vector-borne

transmission

of

larval stages taken up by blood-sucking arthropods or

undergoing amplification in aquatic molluscs (e.g. Onchocerca

microfilariae ingested by blackflies and injected into

new human hosts, Schistosoma eggs release miracidia

to infect snails where they multiply and form cercariae

which are released to infect new hosts). |

| |

|

|

| |

> |

predator-prey

transmission

of

encysted larvae within prey animals (vertebrate or invertebrate)

being eaten by predators where adult worms develop and

produce eggs (e.g. Dracunculus larvae in copepods

ingested by humans leading to guinea worm infection,

Taenia cysticerci in beef and pork being eaten

by humans, Echinococcus hydatid cysts in offal

being eaten by dogs). |

| |

|

|

Taxonomic

overview

Two

classes of nematodes are recognized on the basis of

the presence or absence of special chemoreceptors known

as phasmids: Secernentea (Phasmidea) and Adenophorea

(Aphasmidea). While many different orders are recognized

within these classes, the main parasitic assemblages

infecting humans and domestic animals include one aphasmid

order (Trichocephalida) and 6 phasmid orders (Oxyurida,

Ascaridida, Strongylida, Rhabditida, Camallanida, and

Spirurida). |

| |

|

|

| |

> |

trichocephalid

‘whip-worms’

have long thin anterior ends which they embed in the

intestinal mucosa of their hosts. They have simple life-cycles

where infections are acquired by the ingestion of eggs

and emergent larvae moult and mature to adults in the

gut. Trichuris infections in humans may cause

inflammation, tenesmus, straining and rectal prolapse. |

| |

|

|

| |

> |

oxyurid

‘pin-worms’

have small thin bodies with blunt anterior ends. They

have simple life-cycles, but with an unusual modification.

Female worms emerge from the anus of their hosts at

night and attach eggs to the skin. This causes peri-anal

itching and eggs are transferred by hand to mouth. Infections

by Enterobius cause irritability and sleeplessness

in humans, especially children. |

| |

|

|

| |

> |

ascarid

‘roundworms’

have large bodies with 3 prominent anterior lips. Their

life-cycles involve a stage of pulmonary migration where

larvae released from ingested eggs invade the tissues

and migrate through the lungs before returning to the

gut to mature as adults. Ascaris infections

in humans cause gastroenteritis, protein depletion and

malnutrition and heavy infections can cause gut obstruction. |

| |

|

|

| |

> |

strongyle

‘hookworms’

have

dorsally curved mouths armed with ventral cutting plates

or teeth which they embed in host tissues to feed on

blood. They have complex life-cycles where larvae develop

in the external environment (as ‘geo-helminths’)

before infecting hosts by penetrating the skin. Once

inside, they undergo pulmonary migration before settling

in the gut to feed. Heavy infections by Ancylostoma

and Necator cause severe iron-deficient anaemia

in humans, especially children. |

| |

|

|

| |

> |

rhabditid

‘threadworms’

have tiny bodies which become embedded in the host mucosa.

Their life-cycle includes parasitic parthenogenetic

females producing eggs which may hatch internally (leading

to auto-infection) or externally (leading to transmission

of infection or formation of free-living male and female

adults). Super-infections by Strongyloides

may cause severe haemorrhagic enteritis in humans. |

| |

|

|

| |

> |

camallanid

‘guinea worms’

infect

host tissues where the large females cause painful blisters

on the feet and legs. When hosts seek relief by immersion

in water, the blisters rupture releasing live larvae

which infect copepods that are subsequently ingested

with contaminated drinking water. The ‘fiery serpents’

mentioned in historical texts are thought to refer to

Dracunculus infections. |

| |

|

|

| |

> |

spirurid

‘filarial worms’occur

as long thread-like adults in blood vessels or connective

tissues of their hosts. The large female worms release

live larvae (microfilariae) into the blood or tissues

which are taken up by blood-sucking mosquitoes or pool-feeding

flies and transmitted to new hosts. Onchocerca

infections cause nodules, skin lesions and blindness

in humans, while those of Wuchereria cause

elephantitis. |

| |

|

|

|

| whipworm |

pinworm |

hookworm |

threadworm |

|

|

|

|

|

roundworm |

filarial

worm |

guinea

worm |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Two

subclasses of cestodes are differentiated on the basis

of the numbers of larval hooks, the Cestodaria being

decacanth (10 hooks) and the Eucestoda being hexacanth

(6 hooks). Collectively, 14 orders of cestodes have

been identified according to differences in parasite

morphology and developmental cycles. Two orders have

particular significance as parasites of medical and

veterinary importance.

|

| |

|

|

| |

> |

Cyclophyllidean

cestodes

have terrestrial 2-host life-cycles where adult tapeworms

develop in carnivores (scolex with 4 suckers and sometimes

hooks) while larval metacestodes form bladder-like cysts

in the tissues of herbivores. The larvae of Taenia

spp. cause cysticercosis in cattle, pigs and humans,

while those of Echinococcus cause hydatid disease

in humans, domestic and wild animals. |

| |

|

|

| |

> |

Pseudophyllidean

cestodes

have

aquatic 3-host life-cycles, involving the sequential

formation of adult tapeworms in fish-eating animals

(scolex with 2 longitudinal bothria), procercoid larval

stages in aquatic invertebrates (copepods) and then

plerocercoid (spargana) stages in fish e.g. Diphyllobothrium

in humans, dogs and cats being transmitted through copepods

and fish. |

| |

|

|

|

| Cyclophyllidea |

Pseudophyllidea |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| Two

major groups of trematodes are recognized on the basis

of their structure and development: monogenean trematodes

with complex posterior adhesive organs and direct life-cycles

involving larvae called oncomiracidia; and digenean

trematodes with oral and posterior suckers and heteroxenous

life-cycles where adult worms infect vertebrates and

larval miracidia infect molluscs to proliferate and

produce free-swimming cercariae. Monogenea are almost

exclusively ectoparasites of fishes while Digenea are

endoparasites in many vertebrate hosts and have snails

as vectors. Some 10 digenean orders are recognized on

the basis of morphologic and biologic differences, two

orders are of particular medical and veterinary significance. |

| |

|

|

| |

> |

echinostomatid

fasciolids

(liver flukes) live as adults in hepatic bile ducts

of mammals where they cause fibrotic ‘pipestem’

disease. The parasites proliferate in freshwater snails

and mammals become infected by ingesting metacercariae

attached to aquatic vegetation. Several Fasciola

spp. cause hepatic disease in domestic ruminants and

occasionally in humans. |

| |

|

|

| |

> |

strigeatid

schistosomes

(blood

flukes) are unusual in that the adults are not hermaphroditic

but form separate sexes which live conjoined in mesenteric

veins in mammals. Female worms lay eggs which actively

penetrate tissues to be excreted in urine/faeces or

they become trapped in organs where they cause granuloma

formation. Miracidia released from eggs infect aquatic

snails and produce fork-tailed cerceriae which actively

penetrate the skin of their hosts. Several Schistosoma

spp. cause schistosomiasis/bilharzia in humans. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

< Back to top |

|